FAEDISHISTORY

The history

> THE ORIGINS

> THE MIDDLE AGES AND CUCAGNA

> FROM THE SERENISSIMA TO THE UNIFICATION OF ITALY

> WORLD WAR I AND FASCISM

> FROM WORLD WAR II TO THE PRESENT

> THE MASSACRE OF BAITA TOPLI UORCH

THE ORIGINS

THE FIRST

TRACES OF

HISTORY.

Thanks to the accidental discovery of two researchers, archaeologist Alba Bellina and Doriana Biombardi, who has a degree in literature with an archaeological focus, the human presence in the territory of the municipality of Faedis can be dated between 3000 and 2800 years BC.

A few years ago, at Bocchetta Sant’Antonio, above the village of Canebola, they found some rock carvings in a round and ovoid shape. These are 10 figures of pointed discs, a kind of ‘circles’ with a small hole in the centre, with a diameter of between 10 and 12 centimetres, executed using the direct hammer technique, the traces of which are still well preserved. These are the very first traces of stone drawings by ancient Friulian artists.

These discoveries are in addition to those made by the expeditions of the Friulian Speleological and Hydrological Circle during the 1900s, at the ‘Ciondar des Paganis’ and ‘Foran di Landri’ caves located on the borders of the municipalities of Attimis and Torreano, respectively. In these expeditions, bone fragments, pieces of pottery and flint fragments were found, confirming that human presence in the area dates back to prehistoric times. Apart from these elements, nothing else is known about this period and one has to go as far as the occupation of Friuli by Rome in 183 B.C. to find more consistent traces of a more socially evolved human organisation.

Studying the etymology of certain words indicating places, streams and villages in the municipality, one also finds traces of the passage of the Celts, who occupied Friuli around 500 BC. These traces can be found in Grivò, Canal di Grivò, from ‘Gravone’, ‘Canal de Gravone’ names widely used in southern France, a region formerly populated by the Celts, and also in the ending ‘is’ of Faedis, which although of Latin origin, from ‘fagetum’ beech forest, shows the influence of the ancient Celtic speech substratum.

Thanks to some relevant agricultural development, Faedis was able to avoid the phenomenon of immigration, which characterized the Friulian areas up until the second half of the 20th Century. In the locality of Collevillano, ‘hill of the villa’, there probably must have been a villa or a small cluster of houses belonging to a Roman settler; in fact, in this area there are numerous remains of potsherds, amphorae, and bricks, and in the excavation work of a vineyard at the beginning of the century, the foundations of some houses were also found.

In 1934, when the old floor was removed to enlarge the parish church, some coins came to light, including a sestertius of Domitian, who was emperor from 81 to 96 AD. Faedis was probably an important strategic point, located on the ‘via Cividina’ that led from Gemona to Cividale (traces of this road can be found, covered with earth and stones, at Ca’ Bertossi).

Presumably dating from this period is the construction of a watchtower, located more or less where that of the church bell tower now stands (dating from the Cucagna era, 13th century), which served to control the Grivò valley and communicate, through the system of mirror fortifications, any invasions by barbarians.

The village must have stood approximately where it stands now, well away, as was customary, from the settler’s villa. In fact, the Collevillano area is just over a kilometre from the town centre. The Romans brought vine and olive cultivation to Faedis, which is still practised today.

A section of the Via Pons Sonti, one of the main roads of the Roman period that connected Cividale (Forum Juli) to Tricesimo and then to the Via di Virunum that went up towards Noricum, passed through the southern part of the territory of the Municipality of Faedis. The traces of the route are somewhat visible, even today, observing from above you can see a straight line that passed a few hundred metres above Case Presa and reached Ronchis, and then continued on to Tricesimo. Some sources also date the origin of the settlements of Campeglio and Raschiacco to this period. After the fall of Rome in 476 A.D., a very dark and stingy period followed until 1000 A.D., especially for Faedis. Friuli was continually invaded and occupied by various peoples, including the Lombards, who left traces of their passage in the name of the hill on which Zucco Castle was to be built, the ‘Rodingerius’ hill, which derives from Roding, a word from ancient German.

Analysing the phenomenon of Slavic migrations, which would have led these populations to settle in the mountains of the Natisone and Torre Valleys, it can be deduced that some of the mountain hamlets originated in this period.

THE MIDDLE AGES

AND THE CUCAGNA

After the fall of the Lombard duchy and the subsequent occupation by Charlemagne’s Franks, there was a period that is considered one of the darkest and most desolate for the whole of Friuli. The population was decimated, living in isolated, mostly self-sufficient villages in which the heads of families ruled. In Faedis, the heads of families used to gather near the church of Santa Maria Assunta in the centre of the then small village.

This type of organisation was widespread throughout Friuli around the year 1000. With the birth of the Holy Roman Empire in 962, things began to change.

Friuli was subjugated to the Germanic Empire and Otto I, realising the importance of this border land with an outlet to the Adriatic, decided to strengthen the Church, i.e. the Patriarchate of Aquileia, in order to make it safer and safeguard it from barbarian invasion. But realising that this was not enough, he initiated and fostered the phenomenon of so-called ‘aristocratic colonisation’, i.e. the descent of German nobles loyal to him to whom he entrusted ‘fiefs’, territories that these lords made the local peasant population work.

It was at this time that Odoric of Auspergh, the Carinthian nobleman who in 1027 was to receive a licence from Patriarch Popone to build a castle in Faedis, arrived in Faedis and made his official entry into history.

The nobleman cleverly chose a mountain just above Faedis, probably already the site of a watchtower from Roman times, from which to dominate the Grivò valley and the small village of Faedis.

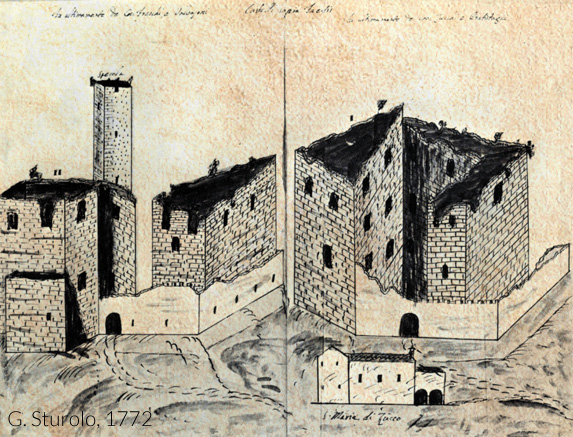

The castle was built on top of the mountain, ‘Cuc’ cocuzzolo, and from this fact comes the name Cucagna given to the castle and the noble family.

The first years of the new lord’s rule were very hard on the poor population who were brutally exploited to settle the fiefdom. Canals were built, streams were dammed, the cultivation of new land began and, of course, the castle was built.

Once the construction of the castle was completed, the Cucagna family received a visit from the Patriarch of Aquileia. This was the beginning of the political rise within the Friulian patriarchal state, which led this noble family to assume one of the most important roles in Friulian feudal history. As a result, Faedis and its territory became an important point in the succession of events throughout the medieval period, but unfortunately also the scene of continuous destruction and fires by the armies of the nobles who from time to time had disputes with the Cucagnas.

The role of the Cucagna family within the patriarchate was very important. They are in fact described as ‘feudal lords

ministerials’ and ‘Camerati’ of the Patriarch and were to provide both during the Patriarch’s lifetime and after his death for the custody and care of the patriarchal chamber, i.e. the treasures of the church.

The family’s political power was undoubtedly due to its excellent relations with the Patriarch, who

He reciprocated the Cucagna family’s loyalty by assigning the various family members increasingly important roles within the organisation of the patriarchy. With

As the years went by, the economic power also increased considerably, as did the fiefs and members of the family, which in time divided into various branches: Cucagna, Partistagno, Valvasone, Zucco, Freschi.

Zucco Castle (from ‘zuc’, hill) was built in 1248 just below that of Cucagna, and until 1326 it was considered one with that of Cucagna. After that date, it was definitively ceded to the Cucagna branch of the family, which took the name Zucco.

The Cucagna family’s political conduct over the years was not very straightforward. It sometimes happened that for reasons of self-interest they made alliances with noble enemies of the Patriarch to whom they had sworn allegiance, and this way of doing things over the years had negative effects for this family.

The last decade of the 13th century saw the formation of two factions of castellans, on the one hand the Savorgnano supported by the ‘della Torre’, ‘de Portis’ etc. and on the other the Cucagna supported by the ‘Attimis’, ‘Strassoldo’, ‘Arcano’ who fought each other for all the following years. Needless to say, the hardest hit by these events was the population of Faedis, who saw their village, crops, fields, etc. destroyed time after time.

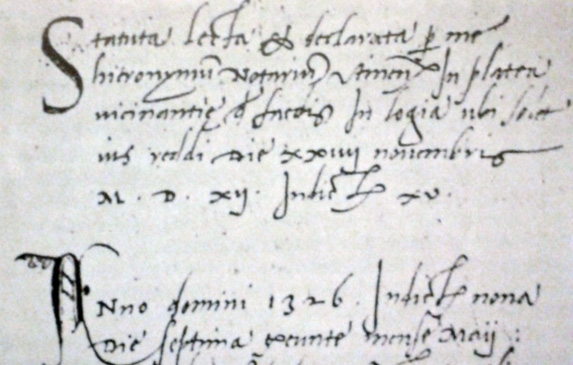

The Cucagna nobles, in an attempt not to lose the support of the population, freed a few servants from time to time, but the most consistent act towards the population occurred on 25 May 1326 when the ‘Statute of the Villa of Faedis’ was issued in which the laws regulating life in the vicinity were written.

The vicinia was the assembly of the heads of Faedis families that included Faedis, Ronchis, Canebola, Costalunga, Canal di Grivò, Pedrosa, Costapiana and Enclosed

(now in the municipality of Attimis).

The penalties ranged from simple fines to the death penalty in the case of murder. This punishment was avoidable if the murderer was forgiven by the victim’s family.

FROM THE SERENISSIMA

TO THE UNIFICATION OF ITALY

At this time, the nobles began to abandon the castles, the borders were more secure and by this time those buildings were not very comfortable. The numerous families of the various branches of the original Cucagna lineage (from the 16th century, the Cucagna family assumed the appellation ‘Freschi’ from Francesco di Cucagna, ‘Fresco’), once they descended to the plains, settled in Faedis, Udine and Cividale. But it is mainly Ronchis that became the fixed abode of the Freschi and the Partistagno family, who built their large villas here.

The transfer of the servants and labourers led to a considerable increase in the population of Ronchis to 150 people. The size of this number becomes clear when one considers that in 1596, the parish of Faedis, which included Faedis, Ronchis, Canebola, Costapiana, Costalunga and Pedrosa, had a population of 850.

The other hamlets of Faedis (Campeglio, Raschiacco, Colloredo, Valle) saw their stories linked to the castello di Soffumbergo, summer residence of the Patriarchs from 1240 until the fall of the Patriarchate. The castle was inhabited by a gastaldo with a fiefdom that the Patriarch kept to guard the manor. This area, thanks to the constant presence of the religious and civil leader of Friuli, enjoyed renown and splendour. In 1420 the castle came under the control of the Strassoldo family and in 1441 it was destroyed by the Cividale people.

In the 1500s, the Friulian lands were again at the centre of fighting, looting and destruction, this time due to the war between the Venetians and the Austrians. The Cucagna family, of Carinthian origin, allied themselves with the Austrians and in 1516 when, after the peace between Venice and Austria, the territory of Faedis returned under the rule of the Serenissima, the Venetians took revenge by burning the castles of the Faedis nobles. This is to be considered a symbolic act, since by then the castles had been abandoned for years. The Venetians’ revenge ended by ousting the Freschi from Friulian political life and relegating them to a marginal role. The years that followed saw a succession of famine and pestilence in Friuli, aggravated by the ever-increasing taxes that Venice demanded to support its wars.

In the 1600s, the Venetians, in order to recover as much money as possible, started to sell communal lands, which were logically bought and then exploited by those who already had money. In 1640, the Colombatti family (citizens of Udine) appeared in Faedis as owners of communal funds, and later the Venetian lords Candeo, of whom traces remain in the name of the mountain behind the schools.

In the 1600s, in addition to poverty and misery, a complex of beliefs, myths and superstitions developed and spread that the official Church tried to combat in every way. This was the period of witches and sorcerers, Martin Luther’s religious reform, etc.. All things that the Church tried to fight through the Counter-Reformation to eliminate heretical ideas and reaffirm Catholic orthodoxy. Witch beliefs also spread in Faedis. In fact, an examination of the acts of the S. Officio collected at the Curia of Udine brought to light the witchcraft trial of a certain Domenica or Menega da Faedis in 1647, who was not convicted.

In the 18th century, Friuli finally saw a slight change in the economic and political situation due to an improvement in living conditions and the decadence of the Venetian institutions. The population increased from 110,000 in the first half of the 17th century to 300,000 in 1750.

The primary reason for this population increase was the beginning of the cultivation of maize, imported from America by the Spanish. The flour that was produced from this plant made it possible to prepare ‘polenta’, a new foodstuff that was richer than the normal diet of the time. This food would be the basis of the peasant diet for many years. Faedis at this time, thanks to the enterprise of Count Gerardo Freschi, saw a piñata factory spring up in its territory, which also exported outside the region. The figure of this nobleman was also very important for the rest of the province, as he was one of the founders in Udine of the Accademia dell’Agricoltura, which aimed to improve and advance the Friulian agricultural system.

The arrival of the French in 1797 changed the political and social reality and the popular mentality of the Friulian people. Unfortunately, the subsequent conquest of Friuli by the Austrians, (on the side map made by the Austrians in the late 1700s and early 1800s) who occupied the region from 1813 to 1866, halted the development of these ideas of freedom, which only began to spread again around 1848, allowing the expulsion of the Austrians and the passage under Italy. The last great famine occurred during this period; in 1816-1817, 151 people died in Faedis in a single year when the average for those years was around 50. Faedis, thanks to Don Antonio Leonarduzzi (the parish priest at the time was considered the non plus ultra of knowledge, culturally the fundamental point of reference), a priest of liberal inspiration, who succeeded in inculcating these values in the people of his parish, turned out to be one of the centres of greatest ferment in the period preceding the annexation of Friuli to the Kingdom of Italy. This was confirmed when, on 21 and 22 October 1866, on the occasion of the plebiscite to sanction the annexation to the Kingdom of Italy, only votes in favour were recorded in Faedis (in the province of Udine there were 104,988 votes in favour, 36 against and 15 null). On 29 December, the first mayor of Faedis, Giuseppe Armellini, was appointed by royal decree.

From then on there was a period of stability that allowed the development of this area to begin. In those years, Faedis had almost 5,000 inhabitants and was considered one of the largest wine-producing areas in the province of Udine. Thanks to its discreet agricultural development, Faedis was able to partially stem the phenomenon of emigration that characterised the Friulian lands until the second half of the 20th century.

SINCE

WORLDWIDE I

TO FASCISM

The Faedo political scene at the end of the 19th century saw the formation of two main orientations: liberals and Catholics. As long as Fr Leonarduzzi was the parish priest, there were no major reasons for friction, because he was liberal-minded, but when Fr Giuseppe Bernich succeeded him, things changed a lot.

This new priest was staunchly anti-liberal and in favour of the Church’s temporalism. The struggle between the two factions flared up immediately: on the one side were the liberals who were formed by the landed and professional bourgeoisie, and on the other those who orbited around the parish. Many episodes of this political ‘war’ ended up at the centre of disputes that went beyond the confines of the municipality, raising a clamour at provincial level, even reaching the benches of the court, as happened in 1905, when the Liberals refused to pay the quartese to don Quargnassi.

The beginning of the century saw Victor Emmanuel III take the throne after the assassination of Umberto I. The new king entrusted the government to the liberal Giolitti. Although his reforms constituted an improvement on previous conditions, they always tended to affect the poorer and poorer classes, who began to form associations with the aim of protecting their interests.

The associations that came into being were of socialist and Catholic inspiration. The former developed more in the cities, the latter were more present in the countryside and rural centres. Faedis, thanks to Don Quargnassi, an inspired priest, saw the birth of three associations that were very important for improving the quality of life of poor people: the Rural Bank on 2 December 1902, the Consumers’ Cooperative on 13 July 1902 and, in the same year, the Social Dairy. Liberals, on the other hand, tended, as was the case in the rest of Italy, to be mainly concerned with protecting their own interests and fighting the temporal power of the Church.

Catholic activism therefore allowed this political party to win the 1902 elections. This led to the escalation of the dispute between liberals and Catholics, which only subsided when Fr Quargnassi left Faedis to go to America in 1909.

The lack of good communication routes kept the country villages in a certain cultural stagnation, and this was also the case in Faedis. People relied more on traditional, pragmatic culture based on experience than on the education provided by schools. Moreover, many were forced to leave school at a very young age to go and work in the fields.

The slow development of Faedo society came to a halt in 1914, at the beginning of the First World War.

The municipality located on the border with the Austro-Hungarian Empire was one of the areas that felt the effects of the war first and most.

In those years the passages of troops who, despite being of Italian nationality, tended to behave very badly: looting, violence and rape by Italian soldiers were not uncommon. This situation worsened when, on 27 October, after the famous defeat at Caporetto (a few kilometres from Faedis), Austrian and German soldiers arrived and oppressed the population with requisitions of livestock and all foodstuffs to cope with the food crisis of the regiments on the various fronts.

The representatives of the population pointed out the exaggerated demands to the Austrian command, but it was adamant. Only after the intervention of the parish priest, Don Mulloni, who shouted: ‘Well, we will give you the grain, but you will have to do us a favour. Bring a machine gun to our square, line us all up and shoot us, so we won’t have the pain of seeing our children, our women and our old men die of starvation”. The position of the Austrians softened and they soon became less demanding.

The arrival of a Hungarian brigade that settled in Faedis from 18 February 1918 was the beginning of a truly terrible period for the population: violence and raids were the order of the day, the very lives of the peasants were endangered. Only with the departure of these soldiers on 22 April did the situation return to normal, so to speak.

Finally on 4 November 1918 came the end of the war. The situation was disastrousIn addition to a high number of deaths, 144 of which 53 in Faedis alone, the continuous raids and destruction brought by each army had brought the country to its knees: houses destroyed, fields ruined, livestock requisitioned by the Germans, etc.. To aggravate this situation also came the Spanish fever that caused the death of another 60 people.

The return of the ‘refugees’, those who had fled when the Austrians arrived, stirred up the Faedese political environment once again. Accusations of ‘Austrianism’ (those who had remained during the Austrian occupation were accused of being in favour of the Austrian government) also affected the clergy, despite the fact that they had been in many cases, as in Faedis, the only point of reference for the population during the period of occupation. This caused a loss of credibility that led to the defeat of the Catholic wing in the 1920 elections.

These were the years of fascism, which did not take long to take hold in Faedis as well, helped by the fact that the town was governed by a coalition that included liberals and ex-combatants. As early as 1922, a section of the Blackshirts was established in the premises below the town hall. Slowly, life returned to normal and reconstruction began.

The Catholic associations, also as a political response to the defeat in the last elections, revived their activism by founding numerous institutions of a socio-economic nature. Those years saw the birth of the kindergarten, the girls’ work school, the town band, the cooperative bakery and the electricity company.

The average standard of living of the inhabitants of Faedis compared to the neighbouring villages was fair. During this period, there was a development of horticulture and a regression of viticulture due to the agrarian policy advocated by fascism. Those who did not emigrate, and the girls who did not go to be maids of the city bourgeoisie, interspersed work in the fields with the cultivation of silkworms and the production of brooms or wicker baskets.

Fascism’s political hegemony did not condition cultural life, where Catholic associationism still held sway. In Faedis, indifference towards the demonstrations organised by the fascists was matched by an increasing presence in the Catholic associations (the parish committee had around 500 members while the youth club had over a hundred adherents). This situation was due to the historical clash between Catholics and liberals, who had become fascists, which originated at the beginning of the 20th century and caused increasing clashes between the two factions.

Giulio Borgnolo, secretary of the local fascio (fascist party), became podestà and managed to avoid conflict and controversy, and thanks to the new political situation, the years leading up to the start of the Second World War passed quite smoothly.

SINCE

WORLDWIDE II

TO DATE

On 10 June 1940, Mussolini let Italy enter the war without adequate military and economic preparation, believing that victory over Germany was now a foregone conclusion. This did not happen and on 25 July 1943 the fascist regime was overthrown.

General Badoglio, who took over from Mussolini in the leadership of the country, stated that Italy would continue to fight alongside Germany, but in the meantime sent emissaries in August to make contact on the terms of the surrender and on 3 September to Cassabile, Sicily, Italy signed the armistice. On 8 September, in a radio communiqué, the government announced the surrender. It was at that time, with the partisan struggle, that Faedis began to play a leading role in the unfolding of the war.

In Friuli, in the marasmus following the signing of the armistice, mainly in the mountains of the central and eastern Pre-Alps, the first partisan units were born to fight the Nazi-Fascists. From the countryside and the cities, young and old, officers and soldiers of the dissolved regular army, militants and clandestines of left-wing parties and anti-fascists in general, went into hiding and formed the first battalions.

In Faedis, already before 8 September 1943, an anti-fascist resistance unit (the first in Italy) had been set up. Called ‘Distaccamento Garibaldi’, it was based above Stremiz and aimed to establish a partisan recruitment centre in the Grivò valley.

The regular army, having become aware of these movements, carried out a round-up and forced the group to move further east towards the ‘Collio’, where they temporarily disbanded and then joined the ‘Garibaldi’ battalion formed on 10 September 1943, into which all the partisans of communist inspiration converged.

The early days of the partisan struggle did not lead to great successes, they were poorly organised and inexperienced groups, but they were useful in scaring off the Germans who, having realised the partisan presence in the Faedis area, fired 12-15,000 artillery rounds per night into the hills for fear of attack and to make them desist.

The partisan struggle became more and more organised and, also helped by the development of the war, led to the formation of free zones in which partisans were in charge. In Friuli, this happened for the ‘Carnia Free Zone’ and the ‘Eastern Free Zone’. The latter included not only Faedis and its territory, but also the municipalities of Nimis, Attimis, Torreano, Lusevera and Taipana, for a total area of 250 square kilometres.

The ‘Eastern Free Zone’ began to form in June-July 1944, when the Germans were forced to converge most of their troops in other areas. The constitution of these territories free of German occupation and where one could return to a fairly normal life also served as a psychological force, constituting, for the surrounding populations, an incitement to rebellion and collaboration with the partisans to defeat the Germans.

In September 1944, the ‘Eastern Free Zone’ reached its maximum extension of 350 square kilometres.

The partisans fighting in Friuli formed two divisions, the ‘Garibaldi’ and the ‘Osoppo’. The first, of communist inspiration, saw the partisan struggle as a people’s struggle of which the partisans were the armed expression, while for the second, made up of men from the Action Party and Christian Democrats, the partisan struggle had to be conducted by trained men far from population centres so as not to cause harm to the population. These differences never allowed the union of all partisans into a single group, which would have been easier to organise.

At the end of September 1944, the Germans decisively tackled the problem of free zones and used a contingent of 29,000 men for this. The partisans, outnumbered in means and men, numbered around 3,000. Unfortunately, they were defeated and the counter-offensive ended with the burning of the villages of Faedis, Nimis and Attimis. In Faedis there were 84 houses burnt, 16 civilians killed, 91 deported, 17 of whom never returned home, and 300 homeless.

The population was prostrate and the partisans had demonstrated the inadequacy of their organisation; while the Garibaldi fell back towards Collio, the ‘Osoppo’ formations dispersed into the Grivò valley. The winter of 1944-45 was very hard and the homeless population was helped by people from neighbouring municipalities and the Friulian lowlands.

After the reconquest by the Germans, there were garrisons of Cossack garrisons in Faedis that terrorised the people with looting, violence and rape.

February 1945 was the scene of one of the most atrocious episodes that occurred in these areas during the Second World War: the massacre of Baita Topli Uorch, (better known as Malghe di Porzûs), in which 15 partisans of the ‘Osoppo’ brigade were killed at the hands of a group of Garibaldian gappisti commanded by ‘Giacca’. A few months after this tremendous act, Friuli was also liberated and on 1 May 1945 the bells finally rang out.

Once the war was over, new problems arose, including the organisation of the new state, monarchy or republic. This problem was solved with the institutional referendum of 2 June 1946.

In the municipality of Faedis out of 2775 voters, 1534 were in favour of the republic, 973 of the monarchy, 208 were blank ballots and 40 were void.

Elections were then called to form the Constituent Assembly, which also saw the victory of the Christian Democrats in Faedis, followed by the Socialists.

Also in June, the first votes for the election of the municipal administration were held in Faedis.

Faedis confirmed the orientation expressed in the election of the Constituent Assembly; the Christian Democrats won over the Popular Unity list formed by the Communist and Socialist parties.

The first mayor to emerge from free elections was Giuseppe Pelizzo who, together with his administration and the people of Faedis had to deal with the problems of reconstruction and the social and economic rebirth of the Faedis community so prostrated by the war.

Economic recovery was slow but gradual, although unfortunately emigration resumed. From 1945 to 1959, 1700 people left the municipality to move abroad in search of work. The development of industrialisation drew more and more people to the cities and industrial centres, causing the abandonment of agriculture, handicrafts and the trend towards depopulation, especially of mountain hamlets. After the end of the war, the municipality of Faedis, like the whole of Friuli, began a slow economic, social and cultural development, favoured at last by stability.

On 6 May 1976 at 9 p.m., Friuli was hit by another terrible misfortune: the earthquake. Gemona and Venzone were almost completely razed to the ground, and in the municipality of Faedis, which was included in the band of disaster municipalities, there was serious damage to buildings and houses, but fortunately there were no deaths.

After this fact, the Friulians rolled up their sleeves and within a few years, in addition to rebuilding what had been destroyed, they began an economic development that today makes our region one of the richest in Italy and Europe, after centuries and centuries of misery. The Municipality of Faedis was awarded the Gold Medal for Civil Merit, for post-earthquake reconstruction work. “During a disastrous earthquake, with great dignity, spirit of sacrifice and civic commitment, he tackled the difficult task of rebuilding the fabric of his home, as well as the rebirth of his social, moral and economic future. A splendid example of civic valour and high sense of duty, deserving of the admiration and gratitude of the entire nation.“

Today, Faedis is a quiet village, surrounded by greenery, with a fairly developed economy, especially viticulture, and the population mostly belongs to the middle class.

EXCIDENCE OF

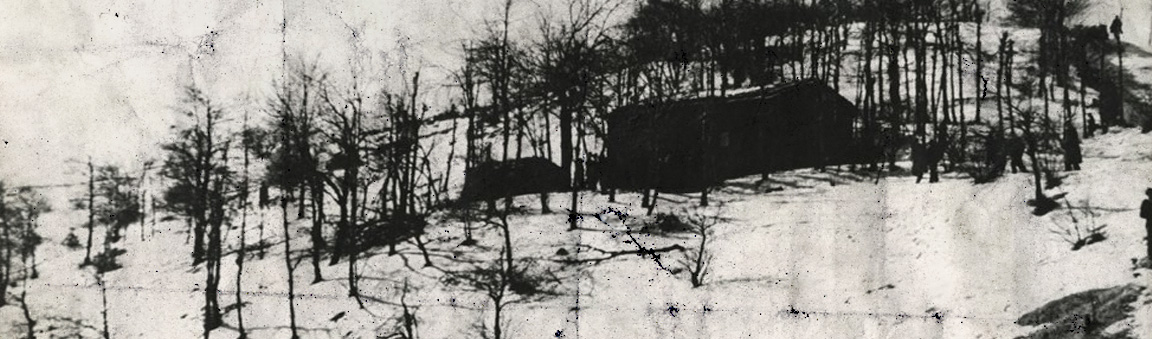

BAITA TOPLI UORCH

7 febbraio 1945 about one hundred Garibaldian Gappisti, commanded by ‘Giacca’ (before the resistance he had already been sentenced for common crimes), reached the Porzûs huts not far from the village of Canebola in the municipality of Faedis, where 17 Osovans commanded by Captain De Gregori (‘Bolla’) and Valente (‘Enea’) were staying. They immediately shot, without reason or judgement, for the faults they attributed to them of ‘intelligence with the enemy’, the two commanders and a woman, Turchetti, indicated as a spy by Radio London. In the following days, in the Romagno Forest, near Cividale del Friuli, they shot the other Osovans, minus two. Among them was the Osovan partisan (‘Ermes’) Guido Pasolini, brother of the famous poet Pier Paolo.

A terrible fact that marks the most disastrous point reached in these lands by the partisan wars. This fact can only find some explanation, certainly not justification, in view of the tormented ideological problematic that exists in this border area. This atrocious episode left a deep mark on the history of the Resistance in Friuli.

Even today, on the first Sunday in February, a commemoration ceremony is held, attended by almost all living Osovani partisans who witnessed that dramatic period.

In 1992, the hut of the massacre was visited by the President of the Republic, Francesco Cossiga. Later, in 1997, director Martinelli made the film ‘Porzûs’ inspired by these events, which caused quite a bit of controversy, but helped to ensure that this sad event was not forgotten.

The Malga di Porzûs will soon receive the certificate of ‘National Monument’.